Exhibition view at MMCA Changdong, Seoul.

Exhibition view at MMCA Changdong, Seoul.

On Distant Objects And Hungry Gods

From social outcasts on the verge of extinction to living human treasures in a matter of just a few decades, Korean female shamans (manshin) and their rituals represent the nation’s most authentic and indigenous form of faith. Medium, magician, healer, fortune-teller, priestess, dancer, musician and spiritual intermediary, manshin today are capable of reaching a supernatural dimension out of which life comes and goes. While in residence at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), artist Jorge Mañes Rubio worked for months with several scholars and female shamans in Seoul, attending many rituals, some of them extremely private and meaningful. Shamans kindly shared their stories with him, stories of struggle and empowerment for these women who still today need to overcome many obstacles and prejudices. Tracing a decisive parallelism between Korean shamanism and a spiritual approach to contemporary art making processes, Jorge Mañes Rubio immersed himself in the revelatory and ecstatic potential of manshin, remaining forever in their debt for all the wisdom they shared with him.

“Back home, if you ask someone what a shaman is, we’ll probably tell you a shaman is someone who lives in the mountains or in the jungle, takes a lot of substances and goes on a trip. That’s the biased idea we have of shamanism. Then you come here to Korea, where shamanism is very much alive and kicking, and it’s quite interesting that in certain circles of academia shamanism is being celebrated because it keeps alive a certain culture. After being persecuted for centuries is now highly supported because it taps into Korean cultural identity. But on the other hand there’s still a lot of prejudice towards it, and is regarded as something not civilised—if you define civilised from a western civilisation perspective. Well, look at western civilisation nowadays, look at Europe and how we dealt with the refugee crisis, look at the United States, look at Brexit… we’re growing more and more jealous of each other cultures, closing up more and more… So what does it mean that shamanism is not civilised? Isn’t being part of an experience, being part of a communal ritual, being part of something that maybe you don’t fully understand—something supernatural and bigger than yourself—isn’t that what civilisation is truly about? About connecting in that special way?”*

We might regard shamans and their practice as something from the past, as beautiful, rare and exotic individuals who preserve a tradition from earlier times. But traditions are constantly evolving, and I would like to think that shamanism could also be part of our future, where a better understanding of each other is being encouraged. The fact that shamanism is not an organised religion does not discredit their significance, on the contrary, to me it makes it all the way more unadulterated and authentic. We usually associate shamanism with fortune-telling, wild rituals and trance-ecstasy phenomenons, but that’s just a very small part of it. During my stay in Korea and thanks to being able to meet some very capable and powerful shamans, I’ve learnt that shamanism is a faith, is a drive that teaches compassion and spiritual balance. A shaman is the mediator who connects both human and spiritual worlds. They are people who profess an unconditional love for nature, firmly trust their indigenous beliefs and aim to live harmoniously with those who surround them. Our world definitely needs more of that.

During the famous PBS TV mini-series “The Power of Myth” Bill Moyers asked Joseph Campbell: “Who interprets the divinity inherent in nature for us today? Who are our shamans, those who interpret unseen things for us?” Campbell replied: “It’s the function of the artist to do this. The artist is the one who communicates myth for us today.” That’s a very powerful influence. Artists might not change the world, but have the power to create small fragments of an alternative world. On the other hand shamans have access to an alternative reality or alternative worlds. I see a decisive parallelism between artists and Korean shamans, we both share the need of rendering the invisible visible.

Jorge Mañes Rubio

*These are excerpts from a public lecture on December 1st 2017 between artist Jorge Mañes Rubio in conversation with curator Bora Hong at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art MMCA in Seoul.

Manshin Kim Keum-Hwa carrying out a ritual at her shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

Manshin Kim Keum-Hwa carrying out a ritual at her shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

“I knew about Jorge’s past work, and knew all about his different projects, nonetheless coming here and looking at his presentation, listening to him, it feels like all the different pieces of the puzzle are coming together. I’m getting to newly realise the works of Jorge and what he means by making the invisible visible; connecting and defining those things that are constant amongst us and making them visible. We actually live in a country run by shamans and however we think that this is something negative and we want to turn a blind eye to it. But it’s precisely celebrating these things what Jorge’s work is centred around. He reminds me of the idea of locus, meaning that there’s a locality, but there’s a universal sign of this locality. This is a contradictory concept but I believe Jorge is very keen at finding these cultural elements that are very local and universal at the same time.”

“Looking at Jorge’s photographs, and the shamanic rituals he was invited to, can you see the expressions on people’s faces? These are happy and very inviting expressions, and I believe this is a mirroring image of Jorge’s face, what you actually cannot see on the screen. I had a chance to attend Jeong Soon Deok’s ritual with him and what I felt is that these people see Jorge not as an exotic individual, but as a person who just absorbs the ritual as what it is. This creates such a positive image about him and that’s why he was invited to so many rituals. I think this mirroring image concept is something very important about his work here in Korea.”*

*These are excerpts from a public lecture on December 1st 2017 between artist Jorge Mañes Rubio in conversation with curator Bora Hong at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art MMCA in Seoul.

Bora Hong is an independent curator, director of Gallery FACTORY (Seoul) and publisher of independent art magazine <versus>.

Dangun, the Legendary Founder of Korea. Embroidery and appliqué on cotton. 180x135cm.

Dangun, the Legendary Founder of Korea. Embroidery and appliqué on cotton. 180x135cm.

Dangun was the legendary founder of Gojoseon in 2333 BC. This is considered the first ever Korean kingdom, located in what now is Manchuria and the northern part of the Korean Peninsula. His is the first story in the Samguk-Yusa (Tales of the Three Kingdoms) compiled in 1280. The story tells how Hwanung, the son of Hwanin, the supreme deity, asked his father if he might be allowed to descend to Earth and live there instead of heaven. Hwanin consented and, giving Hwanung three seals of authority, selected Mt. Taebeck (near North Korea’s Pyongyang) as the best place for his son to arrive and settle together with 3000 followers.

One day both a bear and a tiger came to Hwanung’s residence in prayer and asked to be transformed into humans. The god agreed to this gift but on the condition that they remain in a cave, out of the sun for 100 days and eat only a sacred bunch of mugworts and 20 garlic cloves. The tiger shortly gave up in impatient hunger and left the cave. but the bear – a female called Ungnyo – after only 21 days was transformed into a woman. She longed for a child and so, shortly after the god married her, Dangun was born.

The figure of the bear in the myth probably references the shamanistic beliefs of the nomadic tribes who migrated from the Asian interior in this period and settled in the Korean peninsula, bringing shamanism with them. Dangun may be considered the first Great Shaman who provided a link between the spirit and animal world with humanity. Today, many shamans across Korea still worship Dangun, who represents a symbol of hope for Korean reunification—his celebration day is the only public holiday observed jointly in both Koreas.

This work was made during my residency at the at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Changdong, Seoul. It features several details that have been machine embroidered, or appliqué from second hand clothes and fabrics. The Korean flags have been used here not as a national symbol, but as the way Korean shamans regard it: the taegeukgi, a visual representation of balance between the four different elements, celestial bodies, cardinal directions and seasons.

Dangun, the Legendary Founder of Korea, detail.

Dangun, the Legendary Founder of Korea, detail.

Dangun, the Legendary Founder of Korea, detail.

Dangun, the Legendary Founder of Korea, detail.

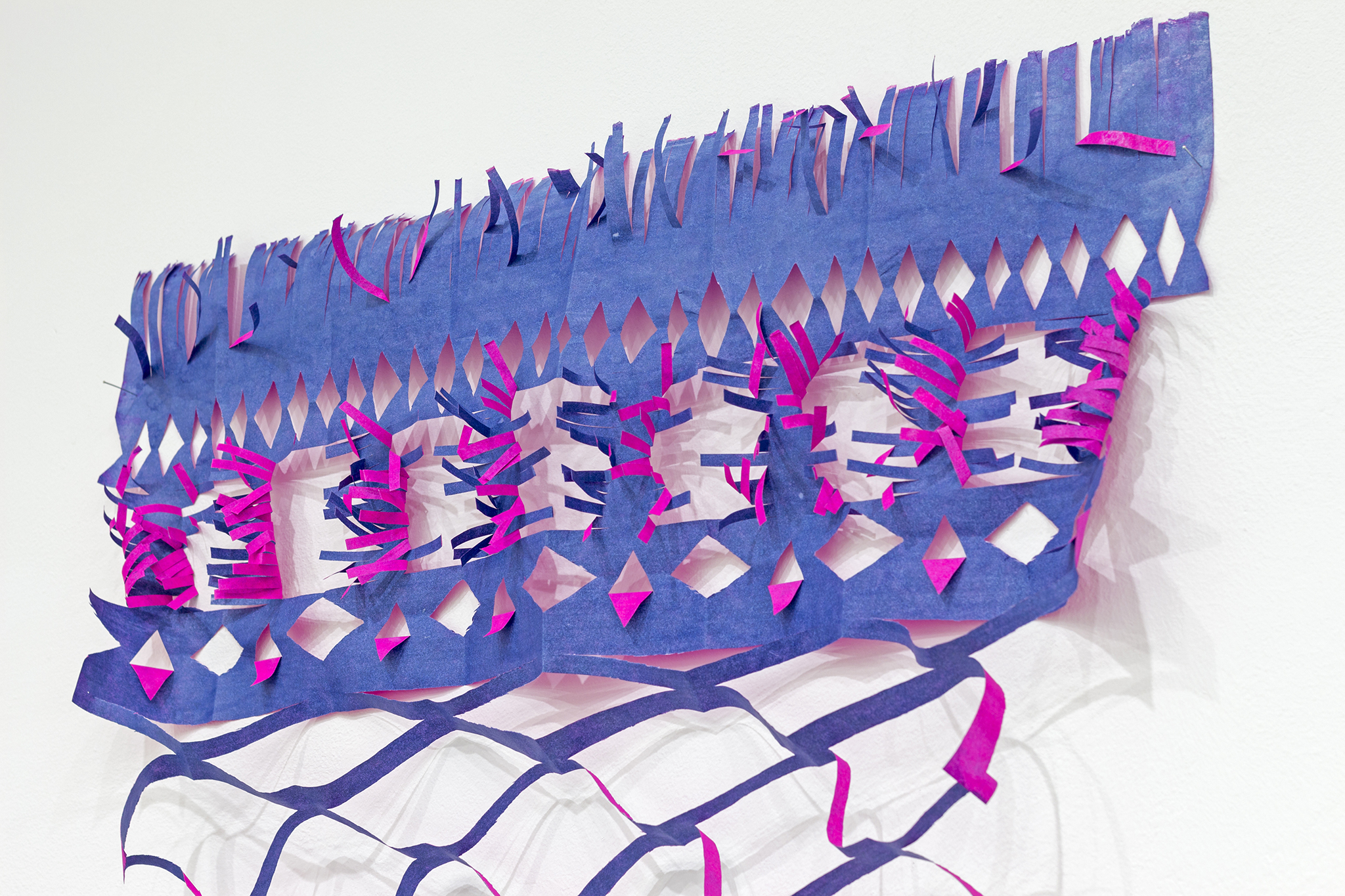

Making the Invisible Visible, pigments on paper, 280x110x70cm.

Making the Invisible Visible, pigments on paper, 280x110x70cm.

Making the Invisible Visible, detail.

Making the Invisible Visible, detail.

Intuition#1, Intuition#2, brass, paper, thread, 90x20x10cm.

Intuition#1, Intuition#2, brass, paper, thread, 90x20x10cm.

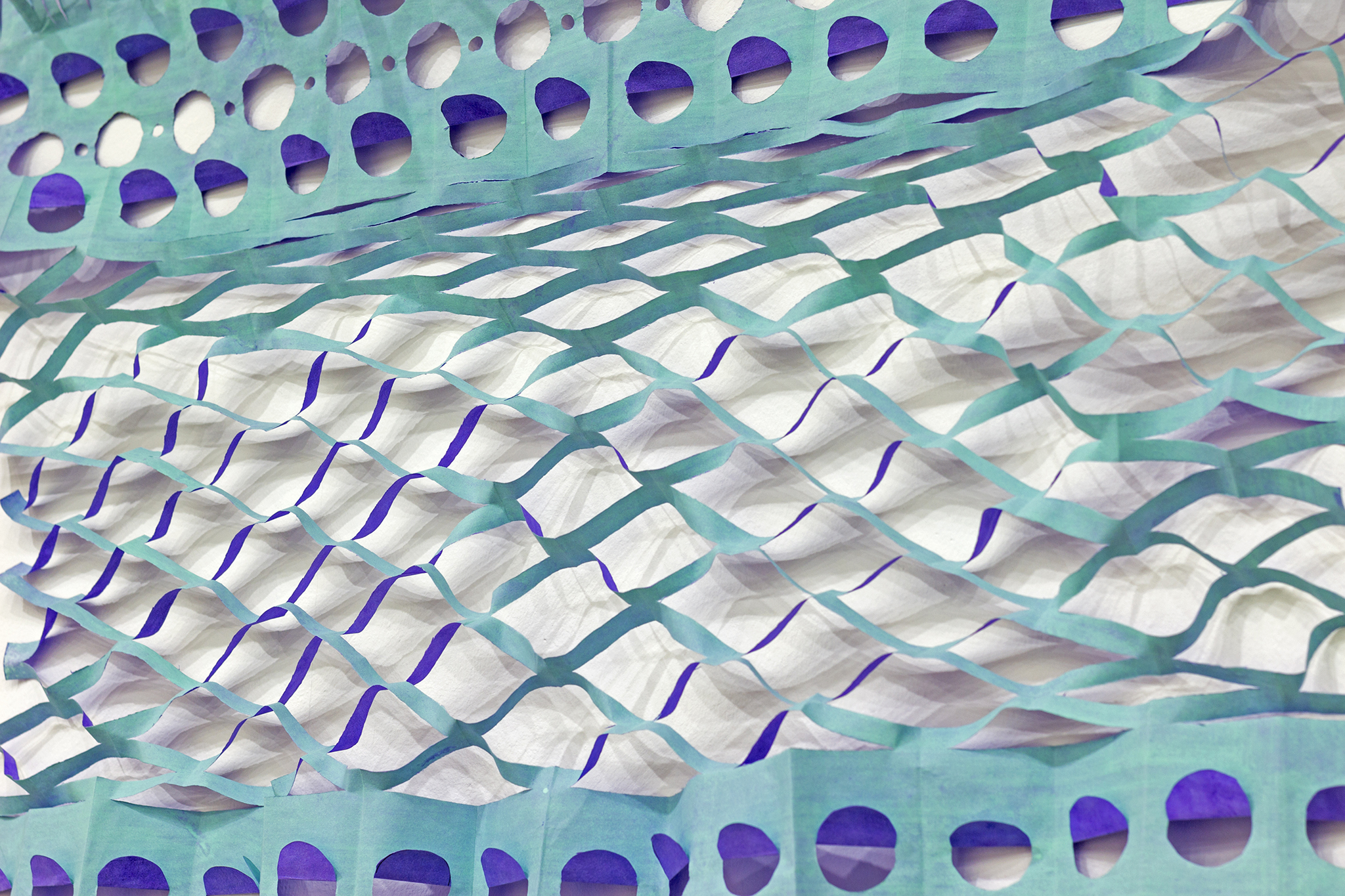

Mediator#1, Mediator#2, Mediator#3, pigments on paper. 130x70cm, 130x70cm, 90x70cm.

Mediator#1, Mediator#2, Mediator#3, pigments on paper. 130x70cm, 130x70cm, 90x70cm.

Mediator#1, detail.

Mediator#1, detail.

Mediator#2, detail.

Mediator#2, detail.

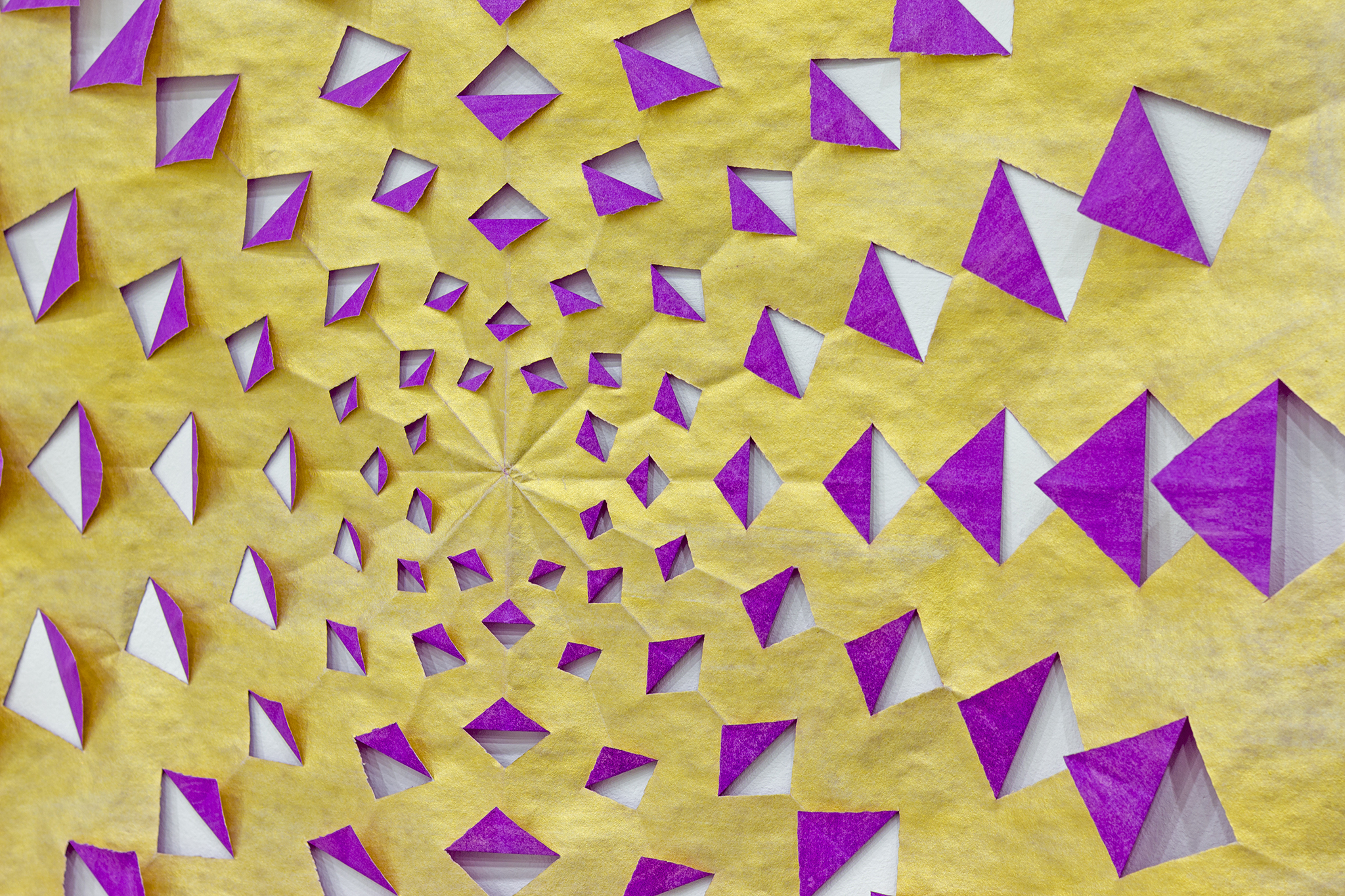

Mediator#3, detail.

Mediator#3, detail.

3 channel video installation at MMCA Changdong, Seoul.

3 channel video installation at MMCA Changdong, Seoul.

Performance at MMCA Changdong, Seoul. Photo: Cheolki Hong. Courtesy: MMCA Residency Changdong

Performance at MMCA Changdong, Seoul. Photo: Cheolki Hong. Courtesy: MMCA Residency Changdong

Performance at MMCA Changdong, Seoul. Photo: Cheolki Hong. Courtesy: MMCA Residency Changdong

Performance at MMCA Changdong, Seoul. Photo: Cheolki Hong. Courtesy: MMCA Residency Changdong

Manshin Kim Nam-Sum carrying out a private ritual in a gutdang near Kookmin University, Seoul.

Manshin Kim Nam-Sum carrying out a private ritual in a gutdang near Kookmin University, Seoul.

Kim Nam-Sum was first struck with Shinbyeong (spirit sickness, predicting a life of shamanism) at the early age of 11. The shaman’s affliction is commonly characterised by loss of appetite, insomnia and hallucinations, a diagnostic hard to explain or treat by western medicine. When she was 21 years old, she got married and moved to Seoul from her hometown Jinju. Kim Nam-Sum started to spend a lot of time at a catholic church and decided to become a nun, but her sickness and hallucinations, including dreams with tigers, dragons and flying horses persisted. Unfortunately her married life was full of tragic incidents, where her husband would abuse her and threaten her constantly. Kim Nam-Sum tried to take her own life several times: “I poured gasoline all over my body but the moment right before I was going to set myself on fire, someone discovered me and saved me. That was God. Now I know that that person was God. I tried to poison myself but failed. Stabbed myself but couldn’t die. It was god, the gods did it. But I didn’t know. Because I didn’t know anything about shamanism.”

At the age of 39, Kim Nam-Sum was tricked by some friends to attend a gut (Korean shaman ritual) on top of Bukhansan Mountain, where they put a red dress on her. Moments later she started clapping, shouting to the skies and the gods. Her sickness suddenly stopped. Kim Nam-Sum was a shaman. She accepted the gods ever since. Today, she’s a well respected shaman who performs in the rare North Korean style from Pyeongan-do. She doesn’t regret accepting the gods, but she is cautious about passing a shamanic destiny to her children: “I don’t have siblings. I have my children, and I don’t want to pass it down to them. So I try my best to be kind and respectful. Not to chase after money or material things. Be proper. But I’m the last Pyeongan-do manshin, and I’m very afraid that after I’m gone this tradition will disappear.”

![]() Manshin Kim Nam-Sum carrying out a private ritual in a gutdang near Kookmin University, Seoul.

Manshin Kim Nam-Sum carrying out a private ritual in a gutdang near Kookmin University, Seoul.

Manshin Kim Keum-Hwa at her shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

Manshin Kim Keum-Hwa at her shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

On a Sunny Friday afternoon I got the chance to meet for the first time Korea’s “national” shaman Kim Keum-Hwa at her Geumhwadang Institute, on Ganghwa Island. Since she’s a spirit mother to many disciples, most people just call her mama. Her efforts preserving and spreading shamanism throughout Korea and the rest of the world are simply incalculable, and today she’s a renowned charismatic shaman and a celebrity in her country. In times when shamanism was brutally persecuted this powerful woman escaped abuse and extreme poverty. Now she’s a well respected figure, designated by the national government as an “intangible cultural treasure” and concerned with pressing political and social issues such as Korean reunification or environmental protection. Spending a few days at her shrine, chatting with her and participating at a unique three days ritual to bless her 70th anniversary as a shaman was an honour and an unforgettable experience. I was also lucky to meet some of the members of her team who were extremely generous to me and helped me further into my project, asking nothing in return. Being able to capture her graceful presence in this intimate portrait was mama’s generous present to me.

Manshin Kim Keum-Hwa carrying out a ritual at her shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

Manshin Kim Keum-Hwa carrying out a ritual at her shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

Offering during a ritual at Kim Keum-Hwa’s shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

Offering during a ritual at Kim Keum-Hwa’s shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

Kim Keum-Hwa’s family carrying out a ritual at her shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

Kim Keum-Hwa’s family carrying out a ritual at her shrine in Ganghwado, South Korea.

Manshin Jeong Soon Deok taking a rest in between a ritual in a gutdang outside Seoul.

Manshin Jeong Soon Deok taking a rest in between a ritual in a gutdang outside Seoul.

Shaman Jeong Soon Deok was born in 1967 into a family that had just moved from North Korea at the time of the Korean War. At the age of 5 her father died and she contracted measles. The infection turned into a long drawn out illness that later on would be diagnosed as Shinbyeong, the spirit-sickness. Jeong Soon Deok would have episodes of hallucinations in which an old man in a white robe and black hat riding a white horse called her name and gave her a long knife, a fan and a bundle of brass bells, iconic shamanic objects. An old woman who lived next door found her trembling after such hallucinations, and quickly identified these episodes as clear shaman-destiny signs. At the beginning, her mother refused such destiny, until a near-death experience of her daughter changed her mind.

Jeong Soon Deok’s father happened to also be a shaman, and although he didn’t perform rituals, he kept a small shrine at home. Before her father died, all this shamanic paraphernalia was buried in a mountain near by. Despite not being aware of this fact, left alone the burial location, Jeong Soon Deok found these objects right before her initiation ritual at the early age of 8, when she became a shaman. At the age of 14 she moved to Seoul, in part thanks to the help of a powerful businessman who was impressed by her accurate divinations. When she was only 16, she became the most promising apprentice of master Korean shaman and Living National Treasure Kim Keum-Hwa. Later on, Jeong Soon Deok would build her own identity as a minjung mudang (a shaman for the people), cooperating with the student pro-democracy movement and even performing for those who were tortured or died in the hands of the military dictatorship. Jeong Soon Deok established herself as a national hero in the eyes of the pro-democracy and Popular Culture Movement groups.

However, the gods grew angry at Jeong Soon Deok because of her political use of the rituals, where in cases holy objects and artefacts ended destroyed by the police. Deities were being polluted with such actions, and all of a sudden the shaman’s word gate was closed. Only after giving in, she could speak again. That was her last performance with student protestors. Later on, Jeong Soon Deok connections with theologians, scholars and even priests of other religions who were engaged in inter-religious movements would confer her a new identity: Korean indigenous saje (priest). Today, Jeong Soon Deok is not only a great and successful shaman, but someone who teaches compassion, peace and respect through her practice. “All the people have their own sufferings regardless of their backgrounds, whether or not they have money… I just want to be a shaman who can give them hope.”

The text above is a compilation of different excerpts from Dr. Kim Dong Kyu, Senior Ressearcher at the Institute for the Study of Religion (ISR), Sogang University.

Manshin Jeong Soon Deok carrying out a ritual in a gutdang outside Seoul.

Manshin Jeong Soon Deok carrying out a ritual in a gutdang outside Seoul.

Manshin Jeong Soon Deok carrying out a ritual in a gutdang outside Seoul.

Manshin Jeong Soon Deok carrying out a ritual in a gutdang outside Seoul.

Manshin Kim Hee Ok carrying out a private ritual at the Guksadang Shrine on Inwangsan Mountain, Seoul.

Manshin Kim Hee Ok carrying out a private ritual at the Guksadang Shrine on Inwangsan Mountain, Seoul.

Manshin Kim Hee Ok carrying out a private ritual at the Guksadang Shrine on Inwangsan Mountain, Seoul.

Manshin Kim Hee Ok carrying out a private ritual at the Guksadang Shrine on Inwangsan Mountain, Seoul.

Manshin Min Hye-Gyeong before carrying out a public ritual at Namhansanseong Mountain near Seoul.

Manshin Min Hye-Gyeong before carrying out a public ritual at Namhansanseong Mountain near Seoul.

Manshin Min Hye-Gyeong carrying out a public ritual at Namhansanseong Mountain near Seoul.

Manshin Min Hye-Gyeong carrying out a public ritual at Namhansanseong Mountain near Seoul.

Public ritual at Namhansanseong Mountain near Seoul.

Public ritual at Namhansanseong Mountain near Seoul.

This project is kindly supported by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea and the Mondriaan Funds